A Woman Clippings 41/72

Charles J. McGuirk, Motion Picture, New York, August 1915.

The Jitney Bus

Words by Edith Maida Lessing, Music by Roy Ingram

Chicago, 1915, Margaret Herrick Library,

Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Part 5

„Plucking three feathers from a lady-chicken“

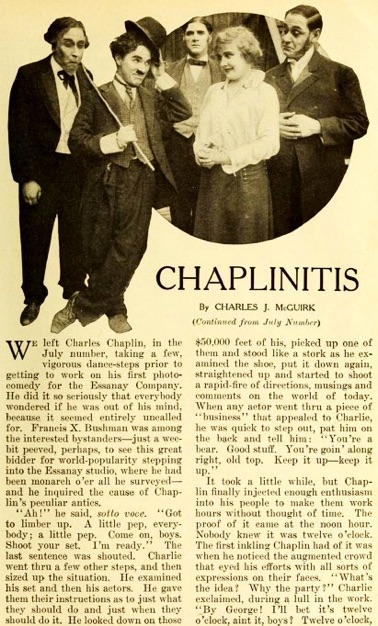

Editorial content. „Chaplinitis

By Charles J. McGuirk

(Continued from July Number)

We left Charles Chaplin in the July number, taking a few,

vigorous dance-steps prior to getting to work on his first

photo-comedy for the Essanay Company. He did it so seriously

that everybody wondered if he was out of his mind,

because it seemed entirely uncalled for. Francis X. Bushman

was among the interested bystanders – just a wee-bit

peeved, perhaps, to see this great bidder for world-popularity

stepping into the Essanay studio, where he had been

monarch o‘er all he surveyed – and he inquired the cause

of Chaplin‘s peculiar antics.

,Ah!‘ he said, sotto voce. ,Got to limber up. A little pep,

everybody; a little pep. Come on, boys. Shoot your

set. I‘m ready.‘ The last sentence was shouted. Charlie went

thru a few other steps, and then sized up the situation.

He examined his set and then his actors. He gave them their

instructions as to just what they should do and just

when they should do it. He looked down on those $50,000 feet

of his, picked up one of them and stood like a stork

as he examined the shoe, put it down again, straightened up

and started to shoot a rapid-fire of directions, musings

and comments on the world of today. When any actor went

thru a piece of ,business‘ that appealed Charlie, he was

quick to step out, pat him on the back and tell him: ,You‘re a bear.

Good stuff. You‘re goin‘ along right, old top. Keep it up –

keep it up.‘

It took a little while, but Chaplin finally injected enough

enthusiasm into his people to make them work hours

without thought of time. The proof of it came at the noon hour.

Nobody knew it was twelve o‘clock. The first inkling

Chaplin had of it was when he noticed the augmented crowd

that eyed his efforts with all sorts of expressions on their

faces. ,What‘s the idea? Why the party?‘ Charlie exclaimed,

during a lull in the work. ,By George! I‘ll bet it‘s twelve

o‘clock, ain‘t it, boys? Twelve o‘clock, sure as you live. That‘s all

for a while. Get out and get your lunches.‘

The actors filed out, tired but very happy. Every one

who had worked with Chaplin that morning had the warm spot

in the heart that comes with the praise of work well done.

When they came back and again took their places on the floor,

there was hardly any holding them they got a piece

of ,business‘ to do. And it was hard to work with Chaplin.

His ideas and methods call for strenuous work.

There are many rough falls and hard tumbles in store for

the actor or actress who works with him and does

his or her role properly. That is why a player will work with

him for a while and then will gently hint that he would

like a rest. Under the spell of Chaplin‘s personality he will wade

thru water, sit in a fire or fall from the third story onto

an asphalt pavement. Away from the little, human dynamo,

he reviews the chances he took, shudders and begins

to feel sorry for himself. Thus it goes in Chaplin‘s life. His work

is an elimination of the unfit and picking of the fit.

Chaplin‘s company right now is a perfect working unit. It is filled

with his personality. That is why his comedy and his

effects are improving all the time. Chaplin‘s gift, like every other

genius‘s, is the making the most of his opportunities

and the welding of his backgrounds into a perfect series

of pictures.

Chaplin is a paradox. He is a character, an ,original.‘

The methods he uses are heavy with the age of centuries, yet

his effects are spectacular and brand new. He is an

Englishman, born in a country which is popularly supposed to be

bereft of humor. While this is a fallacy, nethertheless

Chaplin is not an exponent of British humor. His type is more

the Latin type, and in Anglo-Saxon only in the horseplay

that is inevitable in his plots. There is Celtic subtlety in the Chaplin

comedies that reminds one of the wit of Lever or Swift;

sometimes there is even a hint of Boccaccio or De Maupassant.

The subtleties you do not notice. But they are the things

that tickle you and make your mirth uproarious. When you recall

his pictures, you remember a man being hit by a plate

or a sledge-hammer, or sitting involuntarily in a very active

bonfire. What you don‘t remember is the trick of

expression – the emotions that chase themselves across

the face of the victim – the nonchalance of a pigmy

,giant‘ executing a Herculean feat which you know on the face

of it is absurd and out of the question. That is Chaplin

– subtlety, horseplay, a fringe of pathos, all mixed up in a

bewildering hodge-podge of film that moves you to

unrestrained laughter.

Chaplin‘s beginning was quite humble. There wasn‘t

much apparent chance for his raw talents when he first went

on the stage, as a dancer and as an actor, with William

Gillette. His first appearance in America was a typically English

skit. Thinking it over dispassionately, one wonders how

it ever became so successful. That is, one wonders until one

remembers that Chaplin was in it. It was called A Night

in an English Music Hall, and it portrayed the adventures of a ,drunk‘

who went to a music hall in a hilarious condition and gave

frank and original expressions of opinions on each act he saw.

There was no plot to the sketch. It was merely a rather

crudely constructed vehicle of laughter. Chaplin was ,the funny

drunk.‘ That was the sobriquet he got from enthusiastic

people who remembered him gratefully for the prolonged laughter

he gave them.

An all-wise Moving Picture director came and saw and

was conquered by ,the funny drunk.‘ He offered him a contract.

Chaplin thought it over for about three minutes and

signed up. A week later he had made his début in the ,detestable

slapstick comedy that is rendering coarse the youth

of the country,‘ according to some self-appointed moral

watchmen of a couple of years ago.

In those benighted days, Chaplin comedy was denounced

as wicked, immoral slapstick. His pictures suffered from

the slashing of censors, who figured that this brand of humor

was dangerous. Moral policemen thundered from pulpit,

rostrum and editorial chair that the buffoonery of the Englishman

was silly, inane and perverted. This it distinctly was

not. There was a point to every movement, every situation.

The self-appointed saviors clandestinely saw his

pictures and doubled themselves up in unholy mirth. But, when

they left the theater, they reasoned that, while they could

digest the humor, the poor uneducated masses were likely

to be swayed by the situations instead of the thought

behind them.

But there came a change, gradual and almost unnoticed.

People watched for Chaplin and packed the house

in which he appeared. His star was mounting, altho his name

was scarcely known.

Essanay, realizing the genius of the man, made him

a dazzling offer that was at once accepted. Chaplin enrolled

himself under the banner of that firm. And then the

world went mad. From New York to San Francisco, from Maine

to California, came the staccato tapping of the telegraph

key. ,Who is this man Chaplin? What are his ambitions? What‘s his

theory of humor? Is he married, or single? How does he like

American life? Does he eat eggs for breakfast? Is he conceited?‘

The newspapers wanted to know; the country had risen

and demanded informations.

And in the wake of this demand came the deluge

of requests for the exclusive use of Chaplin‘s figure, or his name,

on a new toy, a song, a novelty in which an image of Chaplin

gravely performed one of his funny stunts. In the theatres, on the

vaudeville stage, comedians stalked gravely on the boards

in crude imitation of the inimitable Englishman. And they were

applauded and appreciated in direct proportion to the

correctness of their imitations. The dignified stage reaching

shame-facedly into the despised Moving Pictures

to lift its comedies into its own audiences. And the ,Chaplin

Waddl,‘ the ,Charlie Strut‘ and the ,Chaplin Wiggle‘

banged and sputtered out of overworked pianos in the song

factories, that have their own methods of showing which

way the wind of popular favor is blowing. Then appeared the

image of the quiet Englishman on the lapels of the

coats of the younger set. Chaplin pins and Chaplin souvenir

spoons were rushed in response to frantic demands

for ,Chaplin favors.‘ The mystic high sign of universal brotherhood

was:,Are you a Chaplinite?‘ And every one knows the

countersign.

Meanwhile, out in the Essanay Western studio, in Niles,

Cal., there was produced a comedy called The Tramp.

It was written and produced by Chaplin, as a vehicle for his

own work. The story was old as the hills; the situations

would have been pronounced crude if they had been worked

by any other than Charlie Chaplin. But there was

something new in the picture. The tramp, after many adventures

characteristic of a city man‘s ignorance of farm life,

fell in love with the farmer‘s daughter, who was nursing

him thru an illness resulting from a wound he got in

defending her home from an attack of thieves.

Down in the projection-room of the Essanay studio,

the men who passed on the picture felt a chill across their backs

as the tramp discarded his humor and became pathetic.

The chill was of fear. Chaplin was stepping out of his province.

The girl‘s real sweetheart appeared on the scene and

was taken into her arms. The tramp saw his air-castles crumbling

into dust. He wrote a note – the crude note of an uneducated

man. He left it on the table, tied up his red bandanna

handkerchief and put it on his cane. He shyly took his leave

of the girl o‘ dreams and started on his journey to world‘s

end. The men in the projecting-room felt the chill give way

to a lump in the throat. The tramp had built too high and

his foolish dream was being shattered. A rather funny situation,

you think? Well, there were tears in the men‘s eyes.

Chaplin had crossed the border into pathos, and had expressed

it solidly and surely. While he was walking down the road,

there was dejection in every movement. But the light-heartedness

of the nomad again gained the ascendancy. Chaplin shook

himself, gave a characteristic flirt of his coat, and wandered jauntily

out of the picture. And the audience smiled, with tears

in its eyes.

What will he do next? Surely not, like Eddie Foy,

will he yearn for the unattainable and attempt to do Hamlet.

His is a genius that bends everything in his touch,

however, and, like David Warfield, who came into public favor

as second fiddle to Weber and Fields, his versatility

may carry him into the field of straight comedy, or comedy-drama,

in such grand characterizations as Warfield‘s Music

Master, which was one of the milestones of theatrical success.

Give Chaplin a great photoplay, a strong, virile, lovable

part, and the brainy little man with the far-away look in his eyes

will astonish and hold us yet with his breadth of a genius

that has just begun to try its first fight of fancy. Out in Niles, Charlie

was informed that another story was being written about

him. Then some showed him his likeness on the cover of a famous

magazine devoted to Moving Pictures, and a third informed

him that a chorus of show-girls, each one costumed à la Chaplin,

was the latest hit on Broadway. Charlie shrugged his

shoulders and looked into space.

,Say,‘ he said. ,Did you see The Tramp? I know I took

an awful chance. But did it get across?‘ Finally he unbosomed

himself to the interviewer. ,Oh, go as far as you like. You‘ll

write what you please, anyway. I‘m trying to figure whether or not plucking three feathers from a lady-chicken will get

by the Censors.‘“

Four photos.

Redaktioneller Inhalt