City Lights 1930 1931 1932 next previous

City Lights Clippings 251/387

National Board of Review, New York, March 1931.

Chaplin Cover, National Board of Review, March 1931, detail

„Hardly the flower-girl of Charlot‘s dreams“

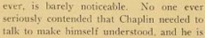

Editorial content. „City Lights“ (...)

„Since Chaplin took to taking his time about turning

out pictures, a new film of his, even if it is just another Chaplin

film, is an event. For the years do not diminish this

little man‘s stature as the greatest clown in the world: anything

he does is exceptional and unique.

City Lights has been long awaited, with even more

than the usual amount of rumor and ballyhoo preceding it. A big

point has been made about its being a ,silent‘ film – silent

in the sense of having no spoken dialogue – a challenge to the

talkies, a crucial event in cinema history.

It turns out to be a delightful film, not Chaplin‘s best but far

ahead of any other funny man‘s best. Charlie is the

familiar Charlot, going through a well rounded out romance,

with the inevitable pathetic ending. It is full of hilarious

episodes and Chaplinesque wistfulnesses and braveries and

gentlenesses. There is nothing in it that quite approaches

the gorgeous pantomime of the sermon in The Pilgrim nor does

does it evoke such yells of laughter as some of The Gold

Rush. But it is a comedy such as no other man under the sun

could make. Judged by the Chaplin best it flags a bit:

it is almost too carefully done, and some of the gags have lost

their old element of surprise. Tumbling into a canal,

balancing unconsciously on the edge of a hole in the sidewalk,

getting paper streamers mixed up with spaghetti – one

foresees too clearly where the laughs are supposed to come

in such situations. There is the Chaplin touch, of course,

but it takes a pretty loyal Chaplin fan not to complain when two

years or more of production yielded so many worn-out

incidents.

As a challenge to the talkies it isn‘t very important.

There is a bit at the beginning that burlesques the kind of sound

that used to come from the screen while the mechanism

of sound reproduction was in its earliest state of imperfection.

For the rest there is no talk, but plenty of sound:

practically any sound that comes handy except that of human

voice. Sometime this arbitrary elimination of the voice

makes odd inconsistencies: why, for instance, do we hear the

orchestra that accompanies a man‘s singing, and not

hear the singing? The omission of dialogue, however, is barely

noticeable. No one ever seriously contended that Chaplin

needed to talk to make himself understood, and he is too skillful

a director not to make his actors as eloquent as necessary

without spoken words. The use of music as an accompaniment

of the action helps to cover the lack of dialogue, too –

though the choosing of music is not one of Chaplin‘s happiest

gifts. And by the way, does the credit line, ,Music

by Charlie Chaplin,‘ mean some of the music, or all of it? The

flower-girl theme has more than a striking resemblance

to the Violet-Seller song that Raquel Meller used to sing, and

some of the other tunes have an oddly familiar ring.

From the production standpoint this picture is probably

Chaplin‘s smoothest and handsomest – it loses

something of the oldtime dash by being so smooth and

handsome. The acting of the subsidiary roles is

excellent – and here again there is a refining, ironing-out

process at work. No more of these almost mythical

creatures with inhuman moustaches and terrifying eyebrows

and sledge-hammer physical prowess! Much of the

atmosphere that used to give Chaplin films an air of being

removed into a world of their own has been sacrificed

for what passes for naturalism in Hollywood.

Even while laughing, one is aware of a faint and uneasy

feeling that Chaplin has been pondering with more

than a bit of solemnity on conventional story values, and it has

led him further than ever into the realms of what is often

called pathetic. Unfortunately the pathos in City Lights is frequently

sentimental and mawkish.

Harry Myers and Hank Mann give comic performances

that would steal scene after scene from almost anybody

but Chaplin. Mr. Myers‘ ,drunk‘ is done with a fine frenzy that

doubles the fun of many episodes, and Mr. Mann

executes his bit in the prize-fight with the skill of a virtuoso.

Only the leading lady falls below Chaplin level: she

is hardly the flower-girl of Charlot‘s dreams.“

Drawing. „Chaplin Again (see page 5)“

Photo. „The place where Charlie saved the millionaire

from suicide.“

Redaktioneller Inhalt

City Lights 1930 1931 1932 next previous