Charlie Chaplin´s Burlesque on Carmen next previous

Burlesque on Carmen Clippings 66/101

Robert Grau, Motion Picture, New York, May 1916.

Management Charles Dillingham, Hippodrome, The Greatest Showplace on Earth Now Presenting Cheer Up! exterior, New York, 1917, postcard

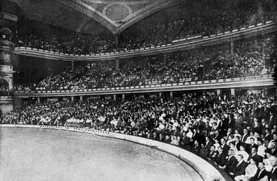

& Hippodrome, auditorium, New York, undated

„Salary“

Editorial content. „The More the People Laughed

at the Idea of Chaplin´s Salary, the More They Had to Pay

By Robert Grau

Theaterdom, which in modern times includes

the movies, still regards the recent exploits of Charles Chaplin

as a gigantic hoax.

The idea that the funniest man in all the world, who

only very recently was appearing in the flesh on the vaudeville

stage at a weekly salary of $100, is to receive now

a weekly pay of $13,500 is so funny that Broadway refuses

to accept the proposition seriously.

But it is an absolute truth not only that this is to be

his weekly wage for the next twelve months but that ever since

Chaplin arrived in New York in a deliberate plan

to bankrupt the nation, the comedian‘s figure has mounted

with such an impetus that there were substantiated

rumors afloat of danger to his life, in that not all of the Motion

Picture magnates who were willing to pay the extraordinary

price could get him.

And these magnates were prepared to pay that price

to keep him from signing with rivals. The dangerous

position of Charley probably accounts for his serious attitude

in negotiating. Not one professional out of twenty

believes that Charles Chaplin is paid $650,000 for his comedy

work on the screen in 1916. While as for the layman,

Chaplin is regarded by him as a great joke. The truth is that

Charles Chaplin could have been signed up for a new

contract at a weekly salary of $1,500 almost any day before

he conceived the plan of paying a visit to Broadway.

It is also true that Chaplin was not accepted with alacrity at

$1,500 a week, so Charley concluded to have a look

at Broadway. That trip to the theatrical Rialto was personally

conducted by the screen comedian‘s oldest brother,

Sidney, who manipulated the cards so well that it is not only

true that Charley is paid $650,000 for one year, but

practically every one of six of filmdom‘s mightiest magnates

was prepared to pay him the same. At no time did

Charley‘s honorarium decline. Why? Because all filmdom

was laughing itself to the bursting point, not at

Chaplin‘s antics, not even at the sight of the real Chaplin

appearing on the Hippodrome stage – they were

laughing at the truly funny spectacle of a screen star, two years

ago hardly known by name, including a half-dozen sane

film barons to pay him more money per week (and every week

of the fifty-two in the year) than was ever meted out

to Edwin Booth, Patti, Caruso and Paderewski in a job lot, and

the more the people laughed, the more serious became

Charley and Brother Sid.

You see it was like this:

Filmdom‘s great funster was not known even by sight

to the people of Broadway. Chaplin was so little known when

he reached the Great White Way that he was mistaken

for everybody but Chaplin. The Chaplin of the screen looks not

a bit like the modest, gentlemanly and serious-minded

man who turned up at midnight on the roof-garden of the

New Amsterdam.

Right then started the tremendous evolution

in the Chaplin salary. When the New York Herald published

an illustrated interview with Charley the people

laughed more then ever. On that day the largest figure

quoted as the comedian‘s salary was about

one-fourth the sum finally paid. It was the publicity

given to Charley‘s rapidly expanding monetary

value, which created the most astonishing theatrical contract

in the world‘s history.

Evidently Chaplin and Brother Sid did not believe

that the public had laughed enough at Charley‘s

contract, so it was not signed, even after all of the film

barons had capitulated to the highest figure

Charley demanded. All of the publicity stunts had added

to the gayety of Broadway, but there was one final

stunt which would convince the film barons that as a contract

manipulator Charley is indeed a genius.

So Charley consented to appear in the vast Hippodrome

on a Sunday evening – appear in the flesh, mark you.

The question or problem as to what the comedian would do to

entertain the Hippodrome audience on that Sunday

evening was so serious that he offered to contribute the $2,000

(which Chaplin was paid for that one night) if he could

be spared from the ordeal. As it happened, he did turn over

the $2,000 to two theatrical charities, but was finally

persuaded to face the public.

Seven thousand persons were packed into

the big auditorium, which has seating accommodations for

4,800; the gross receipts exceeded $7,000 at the

box office. The hotel ticket bureaus did a land-office business

all day Saturday and Sunday. Premiums as high

as ten dollars above the regular box-office price were paid,

and as proving that the real Broadway was attracted

it is stated that on the same Sunday night the Metropolitan

Opera House had the smallest audience of any

Sunday concert in years.

The reason why Chaplin was so long concluding

the momentous document was that all New York was laughing

so much about his salary that Charley decided to keep

the film magnates in suspense. Perhaps some one would pay

Charley an even million for his year‘s work in the

studios, in which case New York would surely laugh itself

to death. As it was. at the eleventh hour, while all

filmdom was holding both its sides, Charley and Sid, as serious

as befits a million-dollar funster, had a conference

with two multi-millionaires who offered to pay him $2,500

a day for a ten-day option on his services, with

a view to launching a $50,000,000 film corporation with

Chaplin at the head. But Charley was afraid that

New York would stop laughing over his contract. Besides,

the world was not to end in 1917. Perhaps it would

be the wiser move to accept $650,000 from a group of practical

film men before the intense humor of the Chaplin contract

begins to modify, and wait until 1917, when Charley can come

hither once more to the Broadway which enriched him.

Then Charley and Sid propose to return to the Great White Way,

when it is hoped that people who never laughed before

at Charley‘s financial conquests will laugh so much and so long

that the Rockfellers and the Fricks, who have already

begun laughing, will call a convention of all the world‘s ,multis.‘

By that time Charles Chaplin‘s vogue as a screen star

will depend not on the laughter he creates in the Motion Picture

studios. Charley must keep the people laughing at his

contracts, and the best way he can attain this goal is to hie

himself at once to movieland, to disappear in the flesh

until his $650,000 has been completed; when, just as surely

as he turns up in 1917, there will be a new nation

of American millionaires camping on his trail. It is certain

if Charley will just reveal himself on one or two

roof-gardens, and begin to quote a seven-figure salary

for 1917, New York will laugh until the humor

of the Chaplin salary becomes contagious again.

But, Charley, never again run the risk you did at the

Hippodrome that Sunday night! You got away with it then, only

because the people were laughing before they saw you,

and they would have laughed even if your performance were

far less unfunny than it was.

But, Charley, you had your nerve with you. Just think

of all that $650,000 stacked up against the chance of a flivver,

and they do say that you were so nervous just before

7 P. M. Sunday that you planned to turn up indisposed, but that

from the Hotel Astor at that hour even the people

were laughing – laughing at that contract, remember!“

Hippodrome, 6th Avenue, 43rd and 44th Street, New York.

Redaktioneller Inhalt

Charlie Chaplin´s Burlesque on Carmen next previous